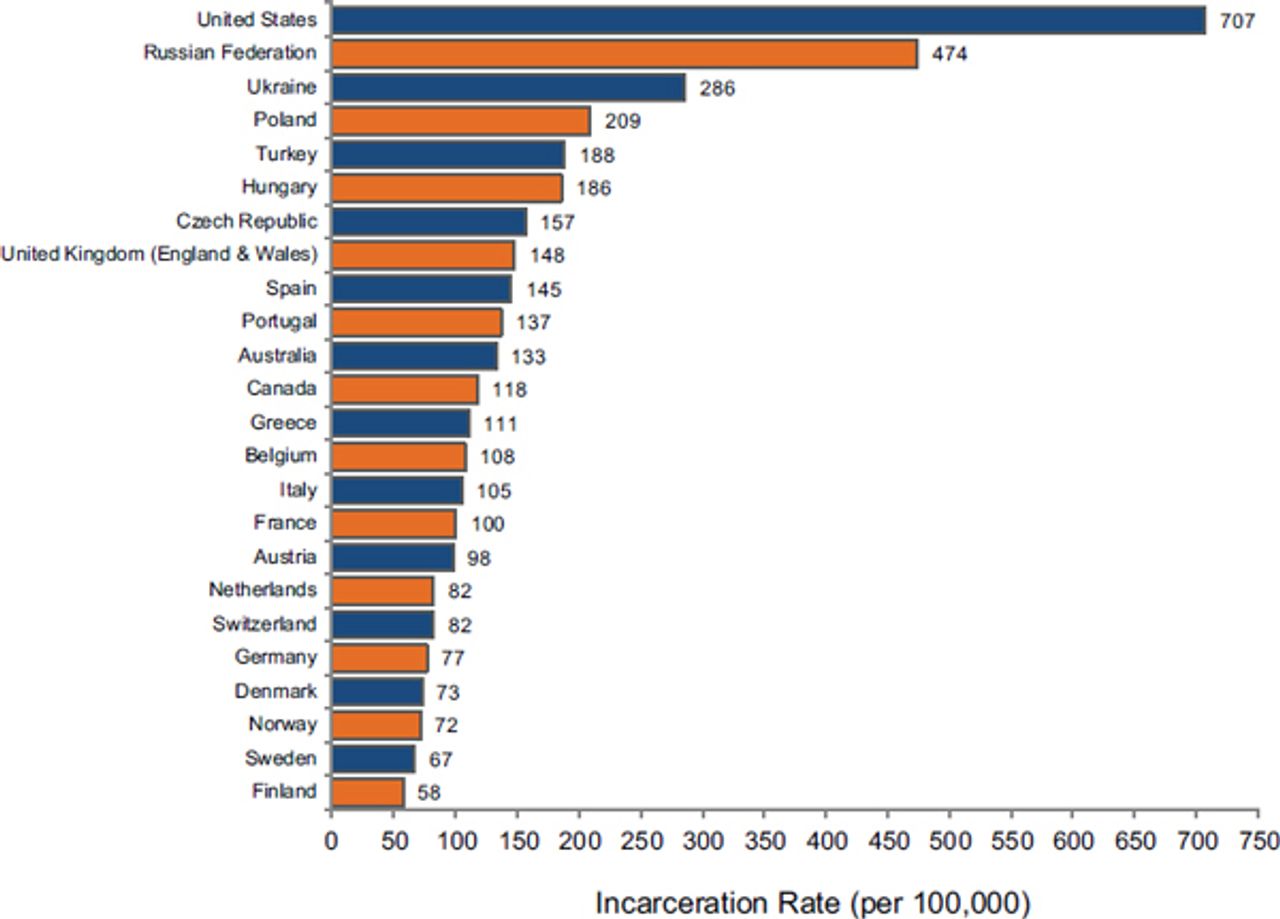

The demographic erosion of Jim Crow through the migration of Southern African Americans to the North increased racial disparity in incarceration through the first half of the twentieth century. Census data show that the incarceration rate among African Americans was roughly twice that of whites. The extent of racial disparity, however, has varied greatly over the past century, following a roughly inverse relationship to the slow incorporation of African Americans as full citizens in American society. African Americans have always been incarcerated at higher rates than whites, at least since statistics were available from the late nineteenth century. Still, it is the profound race and class disparities in incarceration that produce the new class of social outsiders. These years of early adulthood are important not just for a man’s life trajectory, but also for the family and children that he helps support.Īge and sex are the staples of demographic analysis, and the relative youth of the largely male incarcerated population foreshadows much about the effects of mass incarceration. These are key years in the life course, when most men are establishing a pathway through adulthood by leaving school, getting a job, and starting a family. 2 Age intensifies these effects: incarceration rates are highest for those in their twenties and early thirties. Women remain in their communities raising children, while men confront the possibility of separation through incarceration. The incarceration rate has been growing faster among women in recent decades, but the social impact of mass incarceration lies in the gross asymmetry of community and family attachment. Men account for 90 percent of the prison population and a similar proportion of those in local jails. Like criminal activity, prisons and jails are overwhelmingly a male affair. Though the incarceration rate is now nearly eight times its historic average, the scale of punishment today gains its social force from its unequal distribution. In the previous five decades, from the 1920s through the mid-1970s, the scale of punishment in America had been stable at around 100 per 100,000. incarceration rate climbed from 221 to 762 per 100,000. The scale of incarceration is measured by a rate that records the fraction of the population in prison or jail on an average day. Finally, carceral inequalities are intergenerational, affecting not just those who go to prison and jail but their families and children, too. Mass incarceration thus deepens disadvantage and forecloses mobility for the most marginal in society. The inequality is cumulative because the social and economic penalties that flow from incarceration are accrued by those who already have the weakest economic opportunities. As a result, the full extent of the disadvantage of groups with high incarceration rates is underestimated. Prisoners, though drawn from the lowest rungs in society, appear in no measures of poverty or unemployment. The inequality is invisible in the sense that institutionalized populations commonly lie outside our official accounts of economic well-being. The social inequality produced by mass incarceration is sizable and enduring for three main reasons: it is invisible, it is cumulative, and it is intergenerational. The influence of the penal system on social and economic disadvantage can be seen in the economic and family lives of the formerly incarcerated. For these young men, born since the mid-1970s, serving time in prison has become a normal life event.

This inequality produces extraordinary rates of incarceration among young African American men with no more than a high school education. Though the rate of incarceration is historically high, perhaps the most important social fact is the inequality in penal confinement. Yet the scale and empirical details tell a story that is largely unknown. This is a profound institutionalized inequality that has renewed race and class disadvantage. Social and economic disadvantage, crystallizing in penal confinement, is sustained over the life course and transmitted from one generation to the next. As an outcast group, the men and women in our penal institutions have little access to the social mobility available to the mainstream. 1 America’s prisons and jails have produced a new social group, a group of social outcasts who are joined by the shared experience of incarceration, crime, poverty, racial minority, and low education. In the last few decades, the institutional contours of American social inequality have been transformed by the rapid growth in the prison and jail population.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)